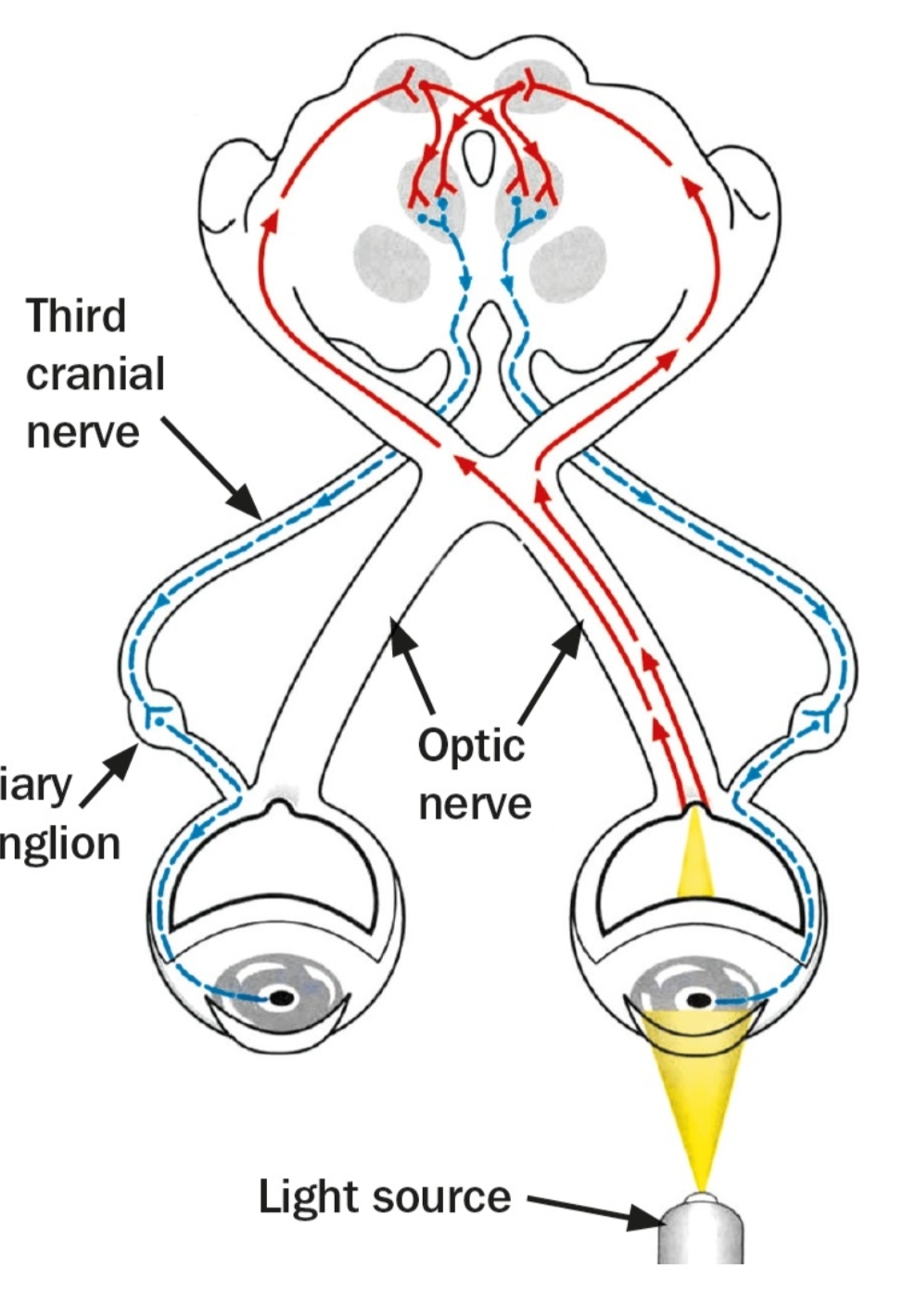

The swinging light test for relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD)

In a normal swinging light test the pupils of both eyes constrict equally regardless of which eye is stimulated by the light ). In an abnormal swinging-light test there is less pupil constriction in the eye with the retinal or optic nerve disease(F.

Steps

Use a bright torch which can be focussed to give a narrow, even beam of light. Perform the test in a semi-darkened room. If the room is too dark it will be difficult to observe the pupil responses, particularly in heavily pigmented eyes.

Ask the patient to look at a distant object, and to keep looking at it. Use a Snellen chart, or a picture. This is to prevent the near-pupil response (a constriction in pupil size when moving focus from a distant to a near object). While performing the test, take care not to get in the way of the fixation target.

Move the whole torch deliberately from side to side so that the beam of light is directed directly into each eye. Do not swing the beam from side to side around a central axis (e.g. by holding it in front of the person's nose) as this can also stimulate the near response.

Keep the light source at the same distance from each eye to ensure that the light stimulus is equally bright in both.

Keep the beam of light steadily on the first eye for at least 3 seconds. This allows the pupil size to stabilise. Note whether the pupil of the eye being illuminated reacts briskly and constricts fully to the light. Also note what happens to the pupil of the other eye: does it also constrict briskly?

Move the light quickly to shine in the other eye. Again, hold the light steady for 3 seconds. Note whether the pupil being illuminated stays the same size, or whether it gets bigger. Note also what happens to the other eye.

As there is a lot to look at, repeat the test, observing what happens to the pupils of both eyes when one and then the other eye is illuminated.

When the test is performed on someone with unilateral or asymmetrical retinal or optic nerve disease, a RAPD should be present. The following happens:

When the light is shone into the eye with the retinal or optic nerve disease, the pupils of both eyes will constrict, but not fully. This is because of a problem with the afferent pathway.

When the light is shone into the other, normal (less abnormal) eye, both pupils will constrict further. This is because the afferent pathway of this eye is intact, or less damaged than that of the other eye.

When the light is shone back into the abnormal eye, both pupils will get larger, even the pupil in the normal eye.

It doesn't matter whether you start with the eye you think has the greater problem or the healthier eye: as long as the light is switched from one eye to the other and back again the signs should become apparent.

Sometimes the RAPD is obvious, as the pupil in the (most) affected eye very obviously gets larger when that eye is illuminated.

OPTOMETRY-SHARP VISION

Optometrist